In the Media

Why So Many Poor Kids Who Get Into College Don’t End Up Enrolling

August 3, 2018

By Alvin Chang

Every spring, millions of students graduate high school with every intention of attending college.

By the fall, an astounding portion of them never show up to college.

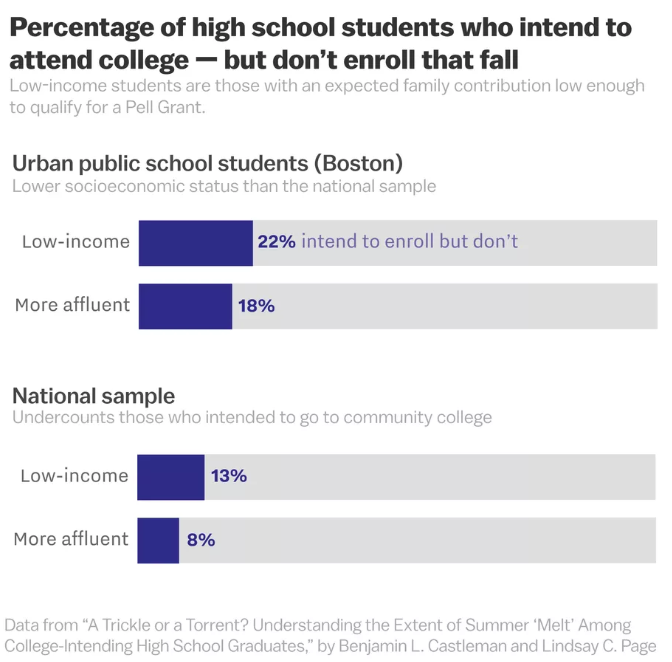

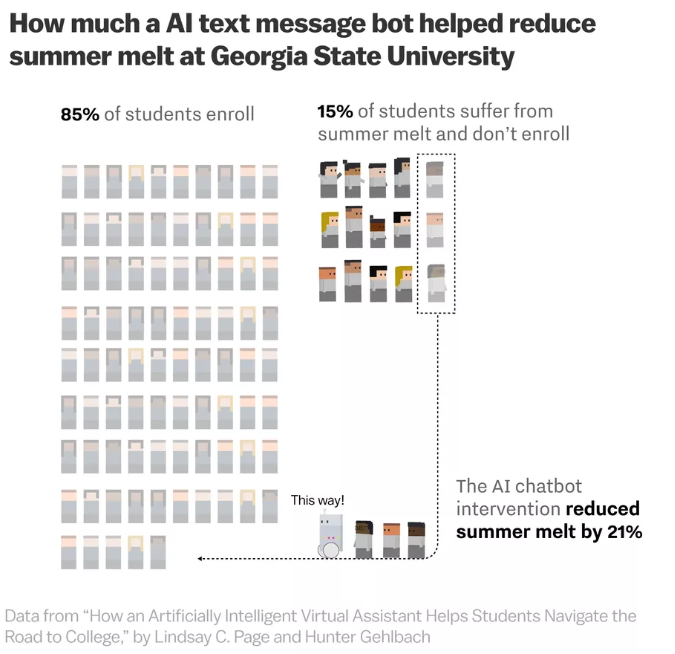

This phenomenon is so common it has a name: “summer melt.” And the effects are stronger for students from a lower socioeconomic background.

Research by Benjamin Castleman and Lindsay Page shows that among students from a lower socioeconomic background, about one in five who planned to attend college don’t actually enroll. The melt rates are lower for more affluent students, but it’s still a significant number.

-(4).png?lang=en-US)

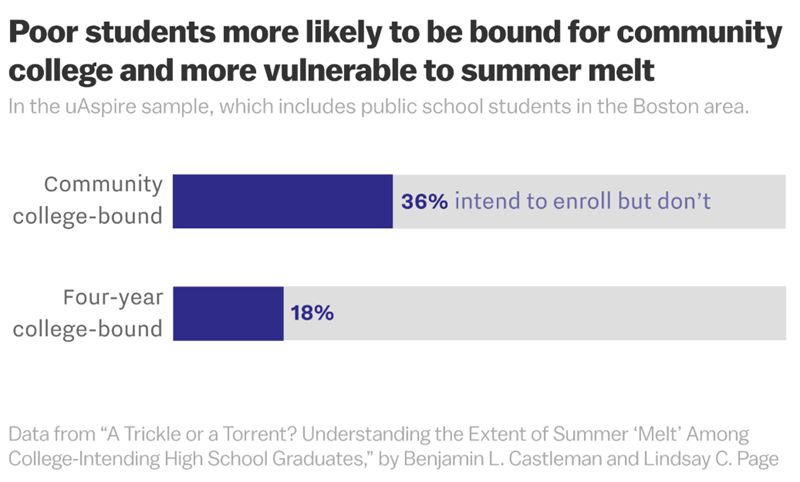

-(4).png?lang=en-US) Much of the gap between poor and affluent students comes from the type of college they choose to attend. Poor kids are more likely to attend two-year community colleges — and the melt rates for those schools is quite high.

Much of the gap between poor and affluent students comes from the type of college they choose to attend. Poor kids are more likely to attend two-year community colleges — and the melt rates for those schools is quite high.

.png?lang=en-US)

This means that a huge number of disadvantaged students — who had to overcome more obstacles than the average student to make it to the doorstep of college — never even go in the door.

”They’ve already made it through so much. They’ve come so far; they’re so close,” said Holly Morrow, who works at uAspire, which helps disadvantaged kids get to college. (uAspire provided data to Page and Castleman for this research.)

So why is this happening?

One high school counselor compared it to the story of Hansel and Gretel. She told researchers that during the school year, the counselors set out bread crumbs for students to follow. But once high school ends, “all of a sudden, the bread crumbs are gone and they have no idea where to go.” And that leads them to drift off the college-bound path.

But as experts have become more attuned to the problem, they have devised new ways to mitigate it. And it turns out that leaving a trail of new bread crumbs is relatively easy — and has dramatic effects on keeping kids on the path to college.

No bread crumbs, no path

During the summer, students don’t have anyone responsible for putting out bread crumbs. This means they have to navigate the path to college by themselves — and they hit barrier after barrier.

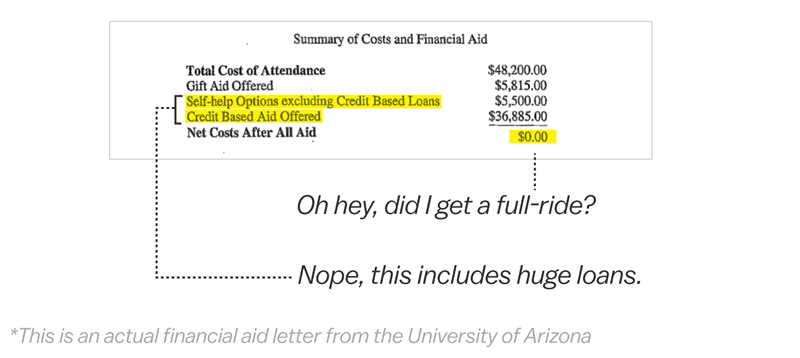

They struggle to decode highly confusing financial aid letters, which don’t make clear how much money they need. They lack the finance background to make huge decisions about money, like taking out thousands of dollars in loans. And since they don’t have a clear idea of the path forward, they often put off key tasks — something all of us do.

”Any kind of complexity can often stop us in our tracks,” Page said. “You must have times where you say, ‘Oh, I don’t want to deal with that thing.’ But when you actually bite the bullet and do it, you think, ‘It wasn’t as bad as I thought it was going to be.’ “

-(1).png?lang=en-US)

So why are some students more likely to get lost in the forest, while others make it through to college?

Page and Castleman found that one huge factor is that some students have a guide: their own parents. If their parents attended college, they can help figure out the difference between, say, a loan and free money. They can tell them what to expect, and answer questions about the experience to come.

Another factor was that some students didn’t have the “soft skills” to call and ask an adult for help navigating the process — especially students from low-income backgrounds, who often had bad experiences asking adults for help, Page said.

Leaving a trail of bread crumbs

This understanding of the barriers helped researchers develop a system that sprinkles and connects those missing bread crumbs.

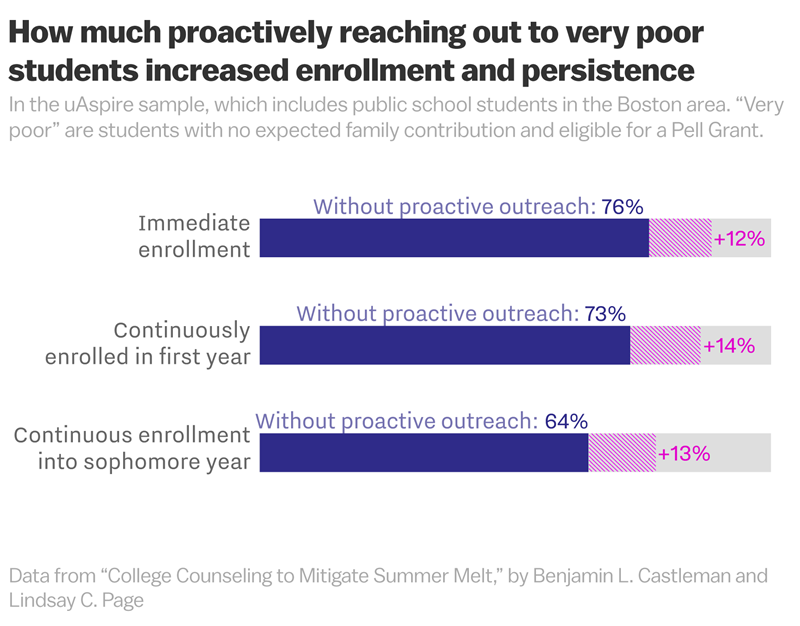

In one experiment, Page and Castleman had counselors proactively reach out to college-bound students during the summer. This intervention had a pretty drastic impact on keeping poor students on the path to college.

.png?lang=en-US)

But it also taught the researchers that the method of outreach was crucial. Phone and email aren’t the best way to reach out to students. They found much more success with texting and Facebook messaging.

These findings were used by a company called AdmitHub in the development of a chatbot that text messages students with reminders about deadlines or required forms, automation that doesn’t drain the limited resources of college financial aid offices. If students needed help, they could interact with an artificially intelligent chatbot rather than a human.

”It feels you’re doing it yourself when a robot’s helping you,” one student told NPR. “It’s like a tool.”

When Page and her colleague Hunter Gehlbach measured the effectiveness of the chatbot at Georgia State University, they found it reduced the percentage of students suffering from summer melt by 21 percent.

.png?lang=en-US)

Page put it another way. She told me the chatbot is “essentially a naggy, knowledgeable parent for kids who aren’t necessarily growing up in households with parents who are knowledgeable about the college-going process.”

Now Georgia State plans to implement this chatbot as a permanent part of its matriculation tools.

We can also smooth the path once disadvantaged students get to college

This summer melt intervention is yet another example of the small nudges that can help disadvantaged students get on an even playing field with everyone else. But the invisible challenges don’t end there — and there are interventions that can greatly help disadvantaged students.

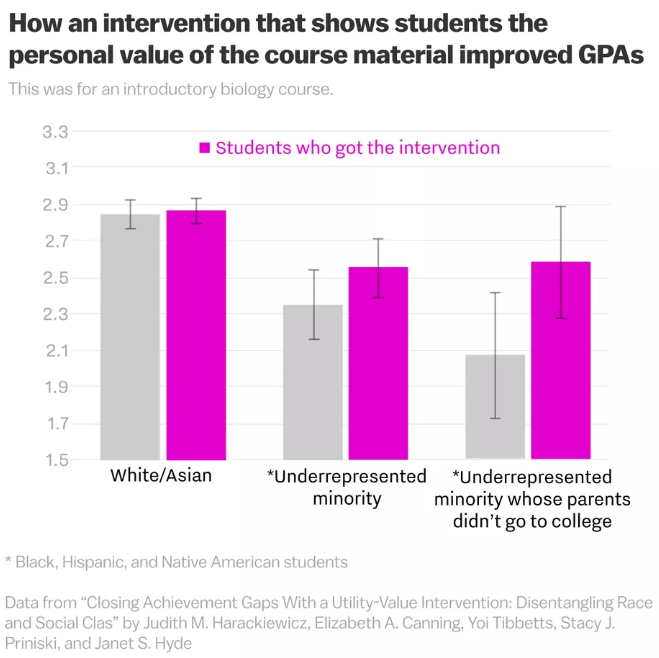

A few years ago, a research team led by Judy Harackiewicz at the University of Wisconsin Madison found disadvantaged students were more likely to abandon degrees in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math) after struggling in a challenging introductory course class, because they either lost interest or felt uncomfortable.

So researchers tested an intervention in which they had students write essays on how the material is personally relevant to them.

That small activity drastically improved the performance of first-generation students who were African-American, Hispanic, or Native American. The researchers suspected one possible reason is that this activity helped them “connect course material to important personal goals.”

.png?lang=en-US)

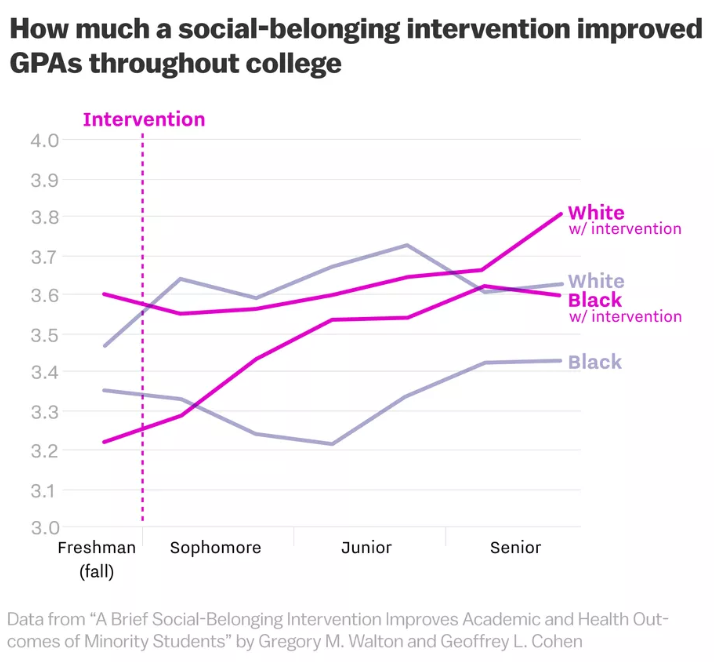

In another experiment, Stanford researcher Greg Walton and his colleague Geoff Cohen theorized that disadvantaged students were concerned about belonging in their college environment — and this social concern was threatening to the point of hurting their academic performance.

So they conducted an intervention in which they put these students in the same room as other students and had them talk through their shared anxieties. The goal was to frame “social adversity as common and transient.”

This intervention was able to close achievement gaps between white and black students over their college careers.

.png?lang=en-US)

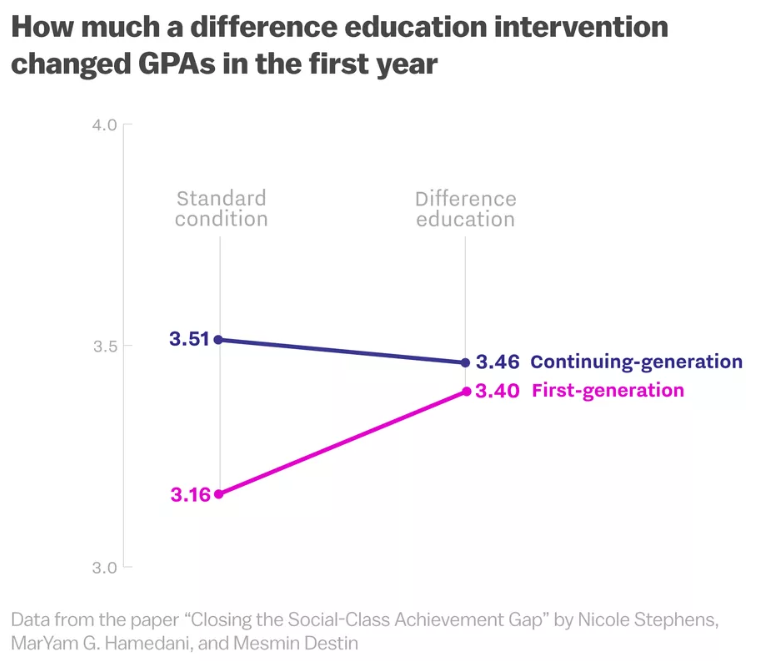

Northwestern University’s Nicole Stephens found that first-generation college students — much like black students — struggle to keep up academically with students who have college-educated parents.

So before the semester, she had students sit in on a session about the importance of their class backgrounds and how it will shape their college experience, which she calls “difference education.” The idea was that this would help them contextualize why they may be experiencing college differently.

This tiny intervention had a striking effect on their outcomes.

.png?lang=en-US)

”The first step is understanding what are the types of obstacles students face in a given context,” Stephens told me. “It comes from an iterative process, which starts with looking at what existing theories and psychology have to say about the question. Then you develop ideas about what might be an effective intervention.”

These interventions work so well because the American education system isn’t designed for the disadvantaged

Walton, the Stanford social psychologist, said the fact that these small interventions work so well reveals just how many barriers there are for disadvantaged kids. “It’s not the America we aspire to,” he said.

These studies show us biases in even the most mundane mechanisms of the American education system, like navigating the summer between high school and college.

”The default cultural environment of a college or university is not neutral,” Stephens said. “But instead the values reflect the perspective of certain groups of students — of those who tend to have more power status in society, which tends to be white middle upper class.”

That said, some barriers to college are much harder to overcome for disadvantaged students, like being academically unprepared or not having the money. These stem from large, systemic issues.

But other barriers cost little to chip away at — which appears to be the case with summer melt.

”This is something that is solvable,” Morrow said.